|

Pets & Farm Animals In Our Place

|

|

Introduction

Sylvie - As my cat curls up on one of his favourite places, my lap and I drift off into that cat-human reverie, I dream not only about the place animals play in the human life, but also what role we play in their lives too.

Last year my cat Hamish became ill. Hamish is a large orange tabby which I rescued from the Lost Cat’s Home. After having him for a couple of weeks I realized that Hamish was not well and took him to the vet. The vet thought he might have a stomach bug, gave him some tablets and sent him home. The next day he had not improved. I took him back to the vet and this time he was kept in for observation. He remained in hospital for five days becoming progressively worse. The vet x-rayed Hamish and found a small object in his stomach. She decided to operate and found a small piece of plastic lodged in the stomach wall. Hamish began to recover almost immediately. While he was in hospital I visited Hamish, and on each occasion, either the vets or the vet nurses commented on how well he was doing after my visits. It was this incident that led to us writing this article.

For the Love of Pets

People have pets for a variety of reasons – pets are sources of affection; they may enhance human self-esteem; they may teach responsibility; and may assist people in socializing with each other. Collis & McNicholas, (1998:117) report that pets give ‘tactile comfort and recreational distraction from worries’; they are ‘less subject to provider burnout’. Besides the main reason we have pets is because they are lovable and give unconditional love.

Katcher and Beck (1988:54) outline that people in the West are being increasingly ‘deprived of opportunities for nurturing and affectionate interchange with others’. They argue that caring for farm animals, pets and gardens gives rise to experiences of nurturing and of being nurtured. The authors contextualize their research in view of the present ecological crisis making a direct link between caring for animals and the need to protect the environment.

It’s not only a lack of opportunity for nurturing. In the community these days there are far less opportunities for connecting with nature especially with wild spaces. So we began to wonder – with the reduction in open spaces in suburbia, with the increasing emphasis on the virtual world, with limited opportunities for engagement with the natural world, can pets provide a bridge between people and nature? Can we learn to care for the earth by caring for our pets?

Connecting with Nature through Caring for Pets

If we are to become better carers of the planet and each other then we need to be engaged to some extent in taking care of our shelter and growing at least some of our own food. Doing this preferably in a cooperative context means that whatever we do helps us to relearn what it means to live with the earth and with each other.

Members were circulated with plans. As there was not sufficient interest we invited and secured expressions of interest form neighbours across the road. Since then Sally, a friesan\airshire cross, on her third calf, has been purchased. She and us are well settled into our patterns. We have back up milkers, and a built in community market for milk, cheese and yogurt.

Sally has been a vehicle for building connections between members and between the cooperative and our neighbours. This cow has helped us to become more one community sharing a mountain top. She has provided a stimulus for neighbours to work together on common projects and for the mountain top community to explore establishing a land care group.

Sally has also been a bridge to make connections to place and seasons. For those of us who commute to the city she provides an opportunity for an intimate relationship with another species through her quieting, reflective qualities. If we have difficulty meditating, one method is to sit in the paddock with the cow and focus on her chewing her cud. I find this is far easier than trying to let thoughts pass through while watching a candle flame.

Research Available

Over the past 15 to 20 years there has been considerable research about the human-animal connection but almost all of it from the human point of view. We have found very little research on the human-animal bond from the point of view of the animal. What little exists is usually anecdotal and from vets who have moved beyond the strict medical model into areas of alternative healing and holistic treatment.

The bulk of the research on the relationship between humans and animals is human-centred. It tends to explore the role of the animal only as it relates to human therapy and well-being, particularly among the elderly, those suffering psychological problems, children with emotional disorders, survivors of sexual assault and the disabled.

A literature search has revealed very little information about the animal side of the human-animal bond, although the wealth of information that is available on the human side attests to the strength of this bond. There is a wide variety of research studies indicating the healing potential of animal companions and wildlife in a range of human crises and illnesses (Cusack, 1988; Katcher & Beck, 1988; Golin & Walsh, 1994; Wells et al., 1997; Brasic, 1998, Wilson & Turner, 1998: Kogan et al. 1999; Cole & Gawlinski, 2000).

In addition, there are a number of articles and news items describing the depth of the bond as animals engage in remarkable acts of heroism to protect their owners, and sometimes, where the owner risks their life to save the life of their pet.

Studies which have looked at the well-being of animals have generally been undertaken in the farm sector to determine the relationship between the care of farm animals and rates of production (Ritvo, 1988). However, Serpell (1986:96-97) quotes one study undertaken by Nerem et al. (1980) on the development of coronary heart disease on laboratory rabbits which shows that rabbits who were played with and touched by their carers had considerably less heart disease than those who were not. James Serpell (ibid.) concludes that this study, as well as other research studies on interspecies contact, show that animals can be calmed and reassured by close relationships with people.

So while there has been detailed research which has documented the success of various therapeutic programs on the health and well-being of people, there seems to have been few in-depth studies on the effect of human contact on the health and well-being of pets, especially on ill, injured or elderly pets.

What evidence we have at this stage is anecdotal from vets, vet nurses and others involved in looking after the welfare of animals. For example, vets and vet nurses at a neighbourhood vet clinic told us that ill pets seem to recover faster when their owners come to visit them. And as well, she said, infirm and aging pets seem to do better with gentle human touch.

It’s a two way thing

If the human-animal bond is seen simply as a one-way relationship, it may not come as surprise that in some circumstances of animal-assisted therapy, the animal becomes an object for human-well-being, treated as a tool and toy and therefore easily discarded. This orientation undermines the relationship between the client undergoing therapy and the animal as a vehicle for human healing. Thus, in order to enhance human healing, the professionals and their client group need to consider both the quality of care as well as the quality of the human-animal relationship.

We have come across a number of articles on pet-assisted therapy where there is obvious reciprocal connection between the owner and the pet but where only one side of the equation has been mentioned. For example, studies on the role of pets in cases of bereavement and divorce have looked at the assistance the pet has provided to the owner going through these life crises, but has overlooked how or whether the pet is also affected by these difficult situations (Allen, 2000; Howie, 2000). Again, there is anecdotal evidence but few detailed studies.

Another an indication of the two way feeling between pets and their owners comes from Astrup et al. (1979, cited by Brasic, 1998:1014), who found that the heart rate of a dog increased when petted by its owner which suggests that ‘animals may exhibit profound physiological responses to familiar friendly people’.

Our hypothesis is that a reciprocal relationship will be more beneficial to humans. We wish to stress the reciprocal nature of the relationship so as not to overemphasize either humans or animals. In this way, we can see that the human-animal relationship can be mutually rewarding to both people and their pets.

References cited:

|

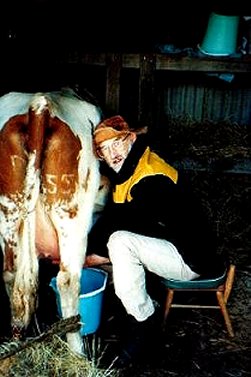

Peter - In the early days at Moora Moora cooperative (see "A Journey through Tracing Roots" in this issue of Gatherings), we had two house cows which were difficult largely because we didn’t know really what we were doing, but for a while we persisted because that is what you do when you are into self sufficiency. Soon we gave up. This time we were better organised. That is we said we will only start a cow cooperative if we have at least 6 shareholders committed to milking once a week.

Peter - In the early days at Moora Moora cooperative (see "A Journey through Tracing Roots" in this issue of Gatherings), we had two house cows which were difficult largely because we didn’t know really what we were doing, but for a while we persisted because that is what you do when you are into self sufficiency. Soon we gave up. This time we were better organised. That is we said we will only start a cow cooperative if we have at least 6 shareholders committed to milking once a week.