|

Is it Ever Too Late? |

|

We were in Port Fairy, Victoria, Australia, to watch the short-tailed shearwaters (rather unromantically called "mutton birds" in Australia). The birds only come ashore in their silent thousands in the evening, so during the cold spring days we explored the surrounding countryside. One of our excursions took us to the exquisitely beautiful Tower Hill State Game Reserve, an island of natural beauty in a sea of farmland near Australia's southern coast. Tower Hill is an extinct volcano containing the hill surrounded by an island-studded lake and wetland. We had a delightful walk and picnic, seeing black swans, an eastern yellow robin, a red-browed finch, a silvereye, a beautiful little blue kingfisher, and many other birds. We also saw a frog, a skink, and a swamp rat. The vegetation and wildlife within this small (614 ha) crater were as varied and beautiful as any we had seen in Australia's larger National Parks. The volcanic geology was fascinating where it could be seen through the verdant native vegetation, although as we walked we could see that the land had been disturbed severely in the past by road-building, dumping, construction, and other human activities. At the visitor centre we learned that the natural wonders of Tower Hill were no more remarkable than the incredible story of its restoration. The story of Tower Hill 1 spans 110 years of thoughtless destruction followed by 40 years of inspiring reclamation. It provides a lesson in how we can work with nature to reverse some of the consequences of human interference.

With the formation in 1958 of the Warrnambool Field Naturalists' Club and the cooperation of the Field and Game Association, the campaign to restore Tower Hill began. Naturalists, hunters, and the Victoria state government wanted to undo some of the past crimes against Tower Hill. Very little was known at that time about the concepts of re-vegetation and habitat restoration. In the words of John Sherwood of Deakin University, "They started revegetating an area -- a large area -- long before anyone knew much about it. They weren't really guided by a philosophy other than to get some native plants back…it was virtually totally defoliated."

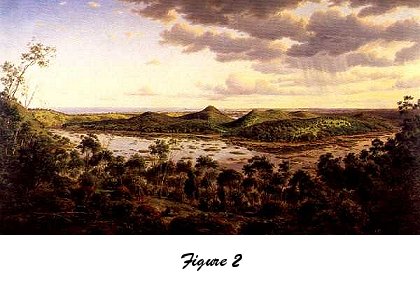

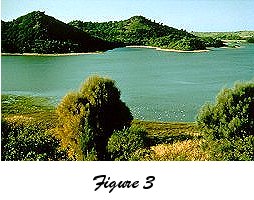

Botanists used the painting as a blueprint for restoration, supplementing it with pollen and soil analysis and knowledge of other volcanoes in Victoria. By 1981 hundreds of school children, naturalists, and other volunteers had planted 250,000 native trees, shrubs, herbs, grasses, and rushes, in the words of John Sherwood, "a quarter of a million trees -- which is a massive amount of trees." In addition to the planting they removed removed vast numbers of introduced plants and worked at restoring the geology. As they did this work, native animal life began to return. Figure 3 4 shows Tower Hill as it appeared in 1981.

Surely getting our fingernails dirty restoring Nature is a core activity in the human-nature relationship. Ecopsychology is not a one-way relationship; we can do more than passively benefit from mindful contact with nature. Elan Shapiro 5 wrote how "environmental restoration work can spontaneously engender deep and lasting changes in people, including a sense of dignity and belonging, a tolerance for diversity, and a sustainable ecological sensibility." I suspect the friends and allies of Tower Hill already know this. They have shown us the way. Tower Hill is a monument both to the wildlife of Australia and to the growing human sense of love and responsibility for Nature. REFERENCES

|

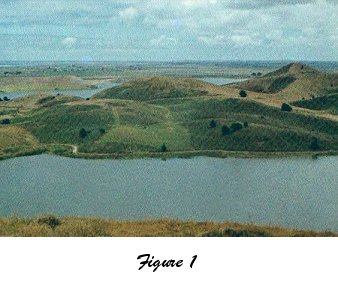

The beauty of Tower Hill was noted very early, as were the destructive effects of human activities beginning with logging and clearing. In 1861 a Mr. Ferguson wrote "The hill itself has also been cleared of the bushy trees which made it so remarkable heretofore." Following the logging came grazing, burning, gravel quarrying, refuse dumping, and the introduction of rabbits, rats, and other exotic animals and plants. Tower Hill was declared to be a national park in 1892 but as unprotected common land the crater continued to be subject to grazing and quarrying despite some public opposition. The only care it seemed to enjoy was the misguided intentional introduction of exotic plants to make it "more attractive". Figure 1

The beauty of Tower Hill was noted very early, as were the destructive effects of human activities beginning with logging and clearing. In 1861 a Mr. Ferguson wrote "The hill itself has also been cleared of the bushy trees which made it so remarkable heretofore." Following the logging came grazing, burning, gravel quarrying, refuse dumping, and the introduction of rabbits, rats, and other exotic animals and plants. Tower Hill was declared to be a national park in 1892 but as unprotected common land the crater continued to be subject to grazing and quarrying despite some public opposition. The only care it seemed to enjoy was the misguided intentional introduction of exotic plants to make it "more attractive". Figure 1

It wasn't clear where to begin until in 1960 a supporter of the project, a Mrs. Winter, said she had a painting of Tower Hill with trees all over it. The painting (Figure 2

It wasn't clear where to begin until in 1960 a supporter of the project, a Mrs. Winter, said she had a painting of Tower Hill with trees all over it. The painting (Figure 2

My partner Linda and I visited Tower Hill in 1993, about 33 years after the restoration had begun. The diversity and beauty of the site was astounding. It was inspiring to witness the ability of Nature, with human help, to recover from destructive human activities. Even more inspiring was the huge community and volunteer effort that made this happen. The people who have spent the last 40+ years restoring Tower Hill can serve as a model to the rest of us. Nature has wonderful recuperative powers which can be unleashed with a little help.

My partner Linda and I visited Tower Hill in 1993, about 33 years after the restoration had begun. The diversity and beauty of the site was astounding. It was inspiring to witness the ability of Nature, with human help, to recover from destructive human activities. Even more inspiring was the huge community and volunteer effort that made this happen. The people who have spent the last 40+ years restoring Tower Hill can serve as a model to the rest of us. Nature has wonderful recuperative powers which can be unleashed with a little help.